Products You May Like

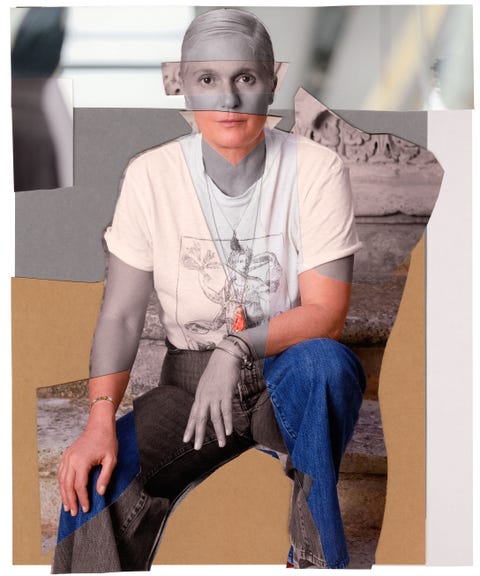

Maria Grazia Chiuri, the creative director of Dior, is looking at me from the sand-gray couch where she is calmly perched in a giant, airy studio in Paris. She’s dressed in jeans, a white blouse, and sandals, with her platinum hair pulled back; around her, everyone is moving. Stylists in face masks consult each other as they study photos on moodboards. Fit models walk down a makeshift catwalk. I try, but fail, to get a glimpse of what, exactly, they are wearing. Chiuri has just released her fall 2020 couture collection as a short film, with models frolicking in ethereal dresses through a lush landscape—online only, the way collections have to be shown during a global pandemic. While the lockdown has been conducive to designing finely crafted, unique pieces, actually making clothes has been tricky. “It’s difficult to travel in Europe. It’s difficult to see things. It’s also difficult to find models,” Chiuri says. “It’s impossible to go fast.”

So she’s been taking it slow. Chiuri collaborated on Zoom with her suppliers and with female artisans in India for her cruise 2021 collection, then livestreamed the show in late July from a piazza in Puglia, in southern Italy. Like the rest of us, Chiuri took a while to adjust to quarantine; she had two different phases. During the first, she was depressed. At the beginning of the pandemic, Italy had one of the highest rates of coronavirus deaths in the world. “I was in Rome, and it was scary being in the center of the crisis,” she recalls. She was following the news constantly, and eventually decided just to listen to it in the evenings. During the second phase, she got back to work. “In Rome, to see the city empty, Venice empty,” was heartbreaking, Chiuri says. “Our economy is tourism and fashion. So for me, it was super-evident that we have to start making something, because we are a big brand and have a lot of workers.” She eventually made her way back to Dior headquarters in Paris to oversee the next collections. Chiuri’s emphasis on craft and female-identified artisanship is not accidental. As with many women of her generation—she’s now 56—Chiuri has developed a deeper awareness of feminism over time. She was born in Rome to parents who were liberal and egalitarian during a time in Italy when women were consigned to traditional roles, and matters like divorce and abortion were controversial. Her father worked for the military, and her mother was a seamstress who ran an atelier. It was out of that openness, and material necessity, that women in her family, including her grandmother during World War II, worked and supported themselves. “I grew up in a family where it was normal to find your job and to think about yourself and your future. They pushed me to study a lot, because they never had that opportunity; for them, to study meant to be free,” she recalls. “I never felt that I could not do something because I was a girl.”

Still, Chiuri rebelled against her parents, who tried to dress her in more feminine attire, by going to flea markets to buy military jackets that she regularly wore with jeans. “The most exciting thing in my generation was to have denim pants and military jackets,” she says, laughing, “to show you’re independent from your family.” When she decided to pursue fashion, her parents were unsure about her choice—design was not considered a serious professional career, and they wanted her to be a doctor, or a lawyer, or something else more conventional and secure. Chiuri went to a public university for two years, because her parents refused to help pay for a private fashion school unless she kept attending the university. (She left the latter after the first two years to focus completely on her fashion studies.) “Everyone thought fashion was a domestic job,” she says. “They didn’t recognize it as cultural and artistic work.”

After Chiuri finished fashion school, she started working for a small shoe company. (Her parents “were surprised that I found a job,” she says. “They said, ‘Ooh, someone paid you for your sketches?’ Yes, I found someone!”) She spent most of the next three decades at two Italian fashion houses: first Fendi, where she and her creative partner, Pierpaolo Piccioli, helped come up with the popular Baguette bag; then Valentino, where she and Piccioli were first accessory designers, and later co–creative directors. Chiuri also made a life in Rome with her husband, Paolo, who owns a shirtmaking atelier, and her two children, both of whom are now graduate students in their early twenties. She enjoyed the privilege of moving through the world without thinking too much about her gender; at Fendi, her first big job, she worked for five sisters in a company that “taught me everything,” she says. So when Chiuri signed on at Dior and the press started hailing her as the house’s first female creative director, it felt strange to think of herself as a symbol of feminism. But she also understood how clothes had greater meaning than just aesthetics: “It’s impossible that it’s not political, something that is in relationship with our bodies.”

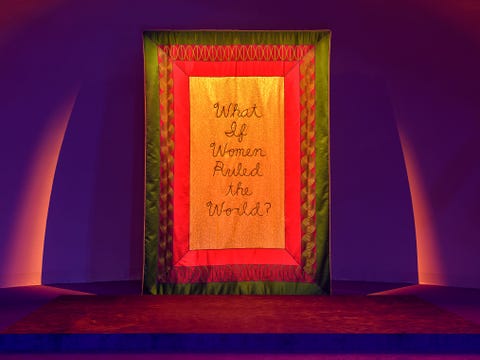

Chiuri’s debut collection for Dior drew inspiration from the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, whose TEDx Talk about feminism had a profound influence. When Chiuri heard Adichie speak about the ways in which adherence to traditional gender roles holds women back, it felt truer to her than anything else she’d heard about the female experience—when Chiuri was young, she thought being a feminist meant you didn’t want to wear lipstick or high heels. In tribute to Adichie’s ideas, Chiuri sent models down the spring 2017 runway in T-shirts printed with the title of her talk—“We Should All Be Feminists”—a well-intentioned move that some critics saw as representative of a lightweight “girlboss” feminism. (It’s worth noting, however, that part of the proceeds from the sale of Dior’s shirts went to Rihanna’s humanitarian nonprofit, the Clara Lionel Foundation.)

A few years later, critics questioned whether Chiuri’s use of West African wax prints in the cruise 2020 show in Marrakech would actually benefit West African designers. In fact, Chiuri had worked with Uniwax, an atelier in the Ivory Coast, to produce the collection, and said she wanted to show how couture could include handmade wax prints, too. For that same collection, she enlisted two Black creators, the designer Grace Wales Bonner and the artist Mickalene Thomas, to reinvent the house’s iconic New Look silhouette. Chiuri has also been collaborating with Indian embroiderers at Chanakya International, a garment house in Mumbai, since she was at Fendi, and she traveled to Nigeria late last year with Adichie to support the author’s “Wear Nigerian” campaign and talk with local designers about business and craft.

Chiuri gets outraged when she thinks about how female artists—all kinds of creative women, really—have often been ignored or disregarded in her home country: “Genius is a man. I never hear of genius women.” Part of the reason she wanted her daughter, Rachele, to study in London, not Italy, was to have the chance to take classes in fields like gender studies. Chiuri herself has been reading books on gender that she never encountered as a student. “She surrounds herself with younger women and listens to them,” says her friend Robin Morgan, the American feminist author and activist. “She says things like, ‘They didn’t teach us about patriarchy in school in Italy. How the hell was I supposed to know?’ ”

Chiuri has said that she considers Rachele her muse. Now a cultural adviser to Dior, Rachele strives to weave feminist theory and the work of female artists into the collections—via collaborations with Judy Chicago and Bianca Pucciarelli Menna, among others. And she has become a sounding board for Chiuri, encouraging her mother—already a proponent of diverse runway casting—to broaden her progressive approach by “supporting local producers and sharing with them the knowledge to improve their own factories, for instance,” she tells me. The two women talk often, with conversational topics ranging from art to movies like Portrait of a Lady on Fire and Lady Bird. “I think I am much more radical than she is, but she’s teaching me to be more nuanced,” Rachele says.

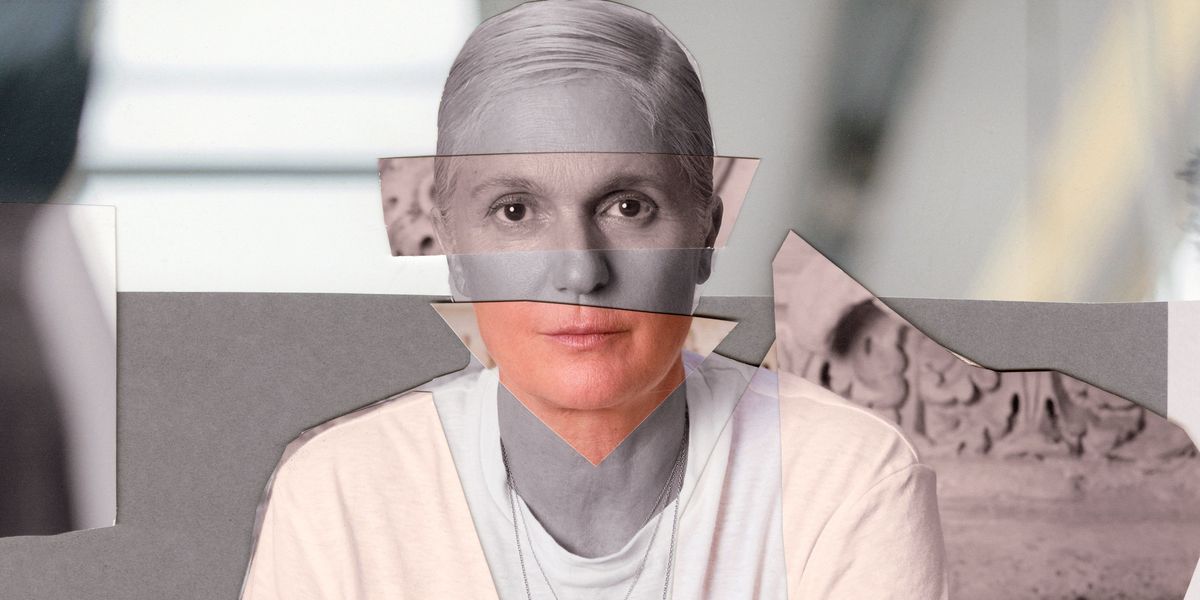

Chiuri also wants to explore the female gaze, especially that of her favorite artists, like Thomas (whose original portrait of Chiuri is seen here) or the Mexican documentary photographer Graciela Iturbide. Her first move at Dior was to hire female photographers, because, she says, “fashion campaigns are mostly done by male photographers—and I think it’s completely different, the way that women look at other women. If Dior hs to speak about femininity, I want to hire women to look at femininity. It’s also very important to me to work with women who have different backgrounds and aesthetic references.” A few years ago, she worked with Iturbide to shoot her Georgia O’Keeffe–inspired cruise collection in Oaxaca for ELLE. “Shooting with her was really dreamy; it was one of the most beautiful moments in my life in fashion,” Chiuri says. “I want to share this platform with other women so that people can also listen to their voices.”

This article appears in the October 2020 issue of ELLE.