Products You May Like

Sixty-six years ago today, Jacqueline Bouvier floated down the aisle of a Newport, Rhode Island, church in ivory silk-taffeta to wed her handsome then-junior senator fiancé John F. Kennedy.

The portrait-neckline gown, with its full bouffant skirt, has been indelibly etched in sartorial history as one of the most iconic wedding-day looks of all time, along with Grace Kelly’s elegant MGM-made bridal frock and Kate Middleton’s dreamy Alexander McQueen creation. Jackie’s dress design was the genius of a little-known Black seamstress named Ann Lowe, who was “way ahead of her time,” legendary Ebony magazine fashion commentator Audrey Smaltz tells ELLE.com. “Someone who was just extremely, extremely talented.”

Lowe—who opened the door for independent designers of all colors and creeds specializing in formal wear—didn’t have an easy path to becoming one of the most sought-after couturiers. She faced constant racial discrimination while working for America’s most elite families, including the du Ponts, the Roosevelts, the Rockefellers, and, of course, the Kennedys.

Lowe was born in Clayton, Alabama, in 1898, with fashion running through her veins. Her grandmother, Georgia Cole, made clothes for her plantation mistress before she was freed in 1860, and her mother, Jane Lowe, specialized in embroidery. Lowe especially loved creating fabric flower adornments, which would later become her speciality. “She learned from them,” National Museum of American History Curator Emeritus Nancy Davis has said. “She was really gifted, but she was also part of this lineage of seamstresses… and really capable ones.”

Together, the three generations of women started a dress company in Montgomery. When her mother died suddenly In 1914, Lowe, at age 16, picked up most of their commissions, including one for the First Lady of Alabama. Word of her superior skills with a needle and thread spread quickly and, three years later, Lowe was accepted to New York’s S.T. Taylor Design School. She had a separate work space from her white classmates, but was often used as an example because of her ability to craft perfectly stitched garments. After graduation, Lowe opened her own shop, Ann Lowe’s Gowns, in Harlem, catering to Manhattan’s social elite. She charged next to nothing for her exquisite designs and soon became known as the Big Apple’s “best-kept secret.”

“I love my clothes and I’m particular about who wears them,” Lowe once told Ebony. “I am not interested in sewing for… social climbers. I do not cater to Mary and Sue. I sew for the families of the Social Register.”

Lowe became acquainted with Janet Lee Bouvier, who commissioned her to create her daughter Jackie’s wedding dress, in addition to all of the bridal party dresses, for the 1953 nuptials.

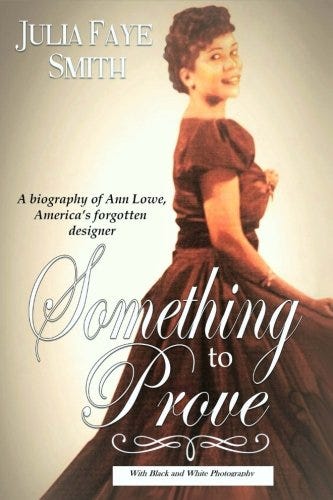

“Ann had designed other dresses and gowns for Jackie and and various members of the Auchincloss-Bouvier family, so she knew their taste and what looked good on each of them,” Julia Faye Smith, author of Ann Lowe’s biography Something to Prove, tells ELLE.com. “When it came time for the wedding, her mother had definite ideas about the type of gown she wanted her daughter to have. Large, elegant fabric, a fairy tale dress. There are questions about what Jackie really wanted and if she liked the final product as much as the world did. Perhaps we’ll never know.”

Inspired by a recent visit to Paris, the bride wanted something simple and French-looking to wear on the big day, however the Kennedy patriarch disagreed. JFK’s father, Joe Kennedy, had final approval on the design.

“Ann did like to please her clients though, and I know she would have wanted the bride to be happy with her gown,” says Smith. “Ann reported conferring with the bride on the design and colors for others in the wedding party, so Jackie probably had some say in the design of her own gown.”

For two months, Lowe and her team of seamstresses, designers, and assistants worked overtime cutting and sewing the gown’s ornate folds made from more than 50 yards of silk taffeta. But just ten days before the wedding, disaster struck: A waterline in their studio broke and spewed gallons of water not only on the bridesmaids dresses, but also on the wedding dress. Everything was ruined.

“Ann, understanding high society at this point, knew that this commission by the bride and her family had to be completed or she would lose her place as Society’s secret designer, and most probably her entire business,” says Smith. ” Wiping tears away and calling on her intrinsic gumption, Ann purchased more of the exquisite fabrics, hired extra help to help her staff, and they all worked night and day to, once again, complete the wonderful assignment.”

Lowe, who expected to net a profit of $700 for her work on Kennedy wedding, actually suffered a $2,000 loss on the assignment after absorbing the cost of the replacement fabric. She never told the bride or the bride’s mother about the incident.

When Lowe arrived in Newport to hand-deliver the gowns, a staff member told her to enter through a service entrance in the back, according to the Smithsonian. She reportedly countered, “I’ll take the dresses back” if she had to use the back door—and walked right on in.

The lavish wedding was written about in nearly every newspaper in the country—and all anyone wanted to know was who designed the dress. When asked, however, Jackie reportedly responded, “a colored dressmaker did it.”

“Years later Mrs. Kennedy was quoted as saying something [else] that Ann felt belittled her to a degree. She wrote Mrs. Kennedy stating her views. Within days Mrs. Kennedy’s secretary called Ann. She explained that Mrs. Kennedy had not seen the final text before publication and did not know that Ann would be referred to as she was in the article,” says Smith. “The White House sought retraction, but the publication never followed up on it. Still, Ann felt no animosity toward the Kennedy’s.”

Lowe and the future First Lady went on to develop a working relationship with “an element of respect and trust between the two,” says Smith. “I’m sure Jackie must have respected Ann’s talent and skill and probably treated Ann respectfully. In turn, this would have resonated with Ann and she would have returned the respect.”

When Lowe began to lose both her eyesight and her business due to back taxes, an anonymous benefactor stepped in to help financially. “Ann always felt it was Mrs. Kennedy, and I like to think it was and that she did so because she had learned of the wedding dress disaster and Ann’s integrity in righting the situation,” says Smith.

When the legendary seamstress died at the age of 82, she was relatively unknown. Her business had floundered beyond repair after fairytale frocks with flounces and flowers went out of style. Her biggest claim to fame, the Bouvier-Kennedy wedding dress, was practically forgotten forever.

Now Lowe is in the spotlight again thanks to a viral tweet from a 19-year-old marketing student. Keshaun Connor, who tweets under the handle @thatssokeshaun, tells ELLE.com he posted a thread about Lowe’s life after coming across her exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

“I’d had the idea for a while,” he says, “and just got a burst of inspiration.”

His tweet has now been liked over 32,000 times and prompted responses like this from Twitter user @Lala_toonice, “I’ve been saying this for years! She was literally one of the first known black fashion designers and her designs were beautiful at that! She had such an amazing personality as well and always did what was best for her soul. She deserved so much more than she received back then.”

“We need to remember Ann as a woman who, in the face of some of great adversity, persevered,” says Smith. “She knew what she was capable of doing, and she worked throughout her life to achieve it. From the Jim Crow South to the skyscrapers of New York, there were obstacles placed before her, but she proved that a designer of her race, or of any race, could become a major designer.”