Products You May Like

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

A friend texted me about this book a few weeks before it came out, asking, “Is this on your radar?” She knows that I love a) forests, b) queerness, and c) books about how wildly queer nature is. She thought I’d love this book, and she was right. If you’re looking for a delightfully earnest, thoughtful, and nuanced exploration of nature, home, belonging, language, queerness, lineage, and how these things intersect, you’re in luck. Or maybe you’re just super into fungi (relatable). Either way, this is a fantastic read.

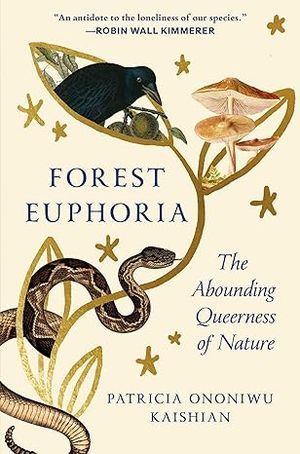

Forest Euphoria by Patricia Ononiwu Kaishian

Kaishian is a mycologist who grew up wandering through the streams and woods of New York’s Hudson Valley. In this book, a blend of science writing and memoir, she recounts her journey into queer adulthood, sharing stories of the animals, plants, and fungi that made her fall in love with science—and see her way into her own queerness.

As a kid, Kaishian saw herself reflected in snakes, turtles, and fungi, even if she didn’t yet have the words to articulate what drew her to these often misunderstood beings. As an adult, she translates that love into a career as a scientist and learns that many of her favorite creatures are even more queer than she realized. She walks readers through the life stories of the plants, animals, and fungi she loves best—glass eels, crows, slugs, turtles, and her beloved mushrooms. She explains just how queer all of these beings are, including how many ways of living, growing, and reproducing they have, how many different sexes and sexual behaviors. In nature, queerness is the norm. The human idea that gender and sexuality can fit neatly into binaries is an anomaly.

Kaishian also writes movingly about her journey of discovery, her childhood in the Hudson Valley, and her Irish and Armenian heritage. She poses many big, impossible questions: What does it mean to love stolen land? What does it mean to be severed from the land of your ancestors by force? How do you forge an honest, nurturing, reciprocal relationship among these ongoing complexities?

She explores these questions through various lenses. I especially loved her writing about language and place. Many languages, including her ancestral languages, Irish and Armenian, are deeply rooted in the landscapes and plants of the places where they emerged. She writes about the violence of languages being severed from their places and the grief she carries about loving a place in a language that does not belong to it.

Kaishian doesn’t answer any of the questions she poses. Instead, she honors them and lives inside them. She talks about “becoming queer to place” in the lineage of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s ideas about “becoming Indigenous to place.” Kimmerer, Kaishian mentions, is one of her own major influences. The whole book is a complicated love letter to all the pieces of the world—languages, trees, mountains, streams, animals, people—who’ve shaped her.

True Story

Sign up for True Story to receive nonfiction news, new releases, and must-read forthcoming titles.