Products You May Like

“How many times have you been subjected to mediocre, romantic, rom-com movies, starring white people?” asks Nepali-American designer Prabal Gurung. “When the AAPI community and minority communities are not just celebrated for their excellence, but allowed to exist in the mediocrity also, that is when we know true inclusivity is happening. You’re allowing them to live.”

As New York City reemerges from its COVID cocoon, Gurung and his fellow vaccinated friends have gathered at Flip Sigi, a West Village restaurant owned by their friend Jordan Andino, that serves Filipino food reworked as familiar American (and Canadian) standards. Oscar de la Renta Creative Director Laura Kim loves the pork belly baos. Gurung is a fan of the breakfast sandwich made with pandesal, a pillowy bread roll that’s a morning staple in the Philippines. Influencer Tina Leung reaches for Adobo wrapped into a burrito and longoniza, a sweet sausage derived from its Spanish colonizers crumbled atop fries and cheese for makeshift poutine. For Asian Americans, it’s a welcome crash of worlds, and blissfully unrelated to “Asian fusion,” the outdated cuisine bastardized and appropriated by celebrity chefs that introduced the west to mandarin chicken salad.

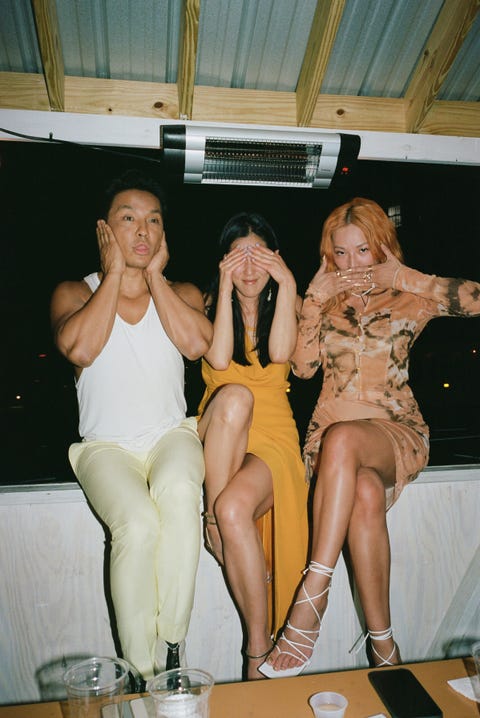

The group digging into the feast make up the self-proclaimed “Slaysians.” In many aspects, the Slaysians are fashion’s real-life Bling Empire. (Socialite Ezra Williams, the youngest of the group and the only one not present that night, starred in the 2019 reality show Rich Kids of Instagram. The title is apt.) We’re used to seeing them all at a distance and on a pedestal, influencer Leung parting crowds during fashion week, Williams on our grids posing with the Hiltons, or watching the three designers close their respective shows in that sprint-bow-run backstage move all humble creatives do. Tonight the silk organza veil is lifted, and this dinner is an intimate gaze into their private and surprisingly casual lives, drinking dirty martinis out of dixie cups. Leung screams “champagne shots!” and lifts each plastic glass to encourage controlled alcohol poisoning. She slices her finger on the exposed neck of the bottle, blood dripping down her diamond rings. “Should I sterilize it with champagne?”

“That’s the reason my phone is always frozen, all these memories,” Kim chimes in, showing all the videos of the group’s escapades on her camera roll. They tickle each other. They craft texts to would-be paramours together. They all chipped in to gift Kim Amina Muaddi heels for her birthday. They tease Lim for hoarding water and air fryers at the beginning of the pandemic. “We never had time to be silly and be like kids, and we are able to be like that with each other,” adds Lim. Andino doesn’t let a cup go unfilled as the night evolves. Like every other #SlaysianDinner, lip-sync performances are held and Gurung heckles sidewalk passersbys to join their dance party.

The origin story of the Slaysians is fragmented, a tangled web of shared acquaintances and social circles going back as early as 2004, when Gurung and Kim first met in an elevator at a fashion building that housed both Bill Blass, where Gurung once worked, and Oscar de la Renta, which Kim now helms with her co-creative director (and best friend) Fernando Garcia. But it wasn’t until Crazy Rich Asians premiered that they realized the power and healing nature of their unity. After Gurung attended a private viewing of the blockbuster film, he reached out to the studio to host a screening for Asians in fashion. Humberto Leon and Carol Lim of Opening Ceremony, Joseph Altuzarra, Claudia Li, Dao Yi Chow, and the three Slaysian designers were all in attendance. “It was the first time that the Asian creatives, designers, editors, stylists [of the fashion industry] came in one place without profiting. We all came together for a cause,” he said. The emotional confrontation of representation on the silver screen instantly bonded them. One movie turned into homecooked dinners, which turned into Bubble_T raves, which turned into intimate evenings masquerading as therapy sessions. Eventually, it whittled down to the five core members, the Slaysians’ hijinks documented on Instagram in grainy photos posted during the late hours of the night.

The meals vary, alternating between Lim’s beautiful recipes he shares on his Stories to takeout to Michelin-star restaurants. The subtle microaggressions in the industry they each experienced and internalized crystallized with every Slaysian Dinner. Emotions were unpacked over a bowl of pho or an Andino-prepared kamayan feast, eaten traditionally with their hands. “It’s a whole cycle of celebration, tragedy, and endearment, all rolled into an evening,” Lim says.

“The narrative that has been told to us, is we’ll need X amount of Asian or minority designers. It’s unsaid, but you understand that,” Prabal says. “Our implicit biases are so influenced by the Eurocentric, colonial lens of what we think chic is. Dismantling that, redefining that, is our job. As creatives of color, we get to redefine what is beautiful”

Being Asian brought them together, but it doesn’t define their friendship. Food is what they really bond over. “It’s not like, ‘Watch out for that shrimp paste,” TK analogizes, about the need to caution non-Asians about fermented pastes or unfamiliar seasonings. “You can just show up and enjoy the food without having to explain the ingredients.” Prabal parrots the same sentiments. “I don’t have to worry about, ‘oh is that spicy’ or ‘is that smelly.’ ‘Is that weird? What are you eating?’ I can eat however I want with my Slaysians.” The flavors they share extend beyond their palettes, with similar lived experiences moving through the world as prime examples of Asian excellence, while actively working to tear down the Model Minority Myth.

“If you’re constantly pressuring and only celebrating minorities when they’re excellent, what you’re doing is saying that they are there for your entertainment,” reasons Prabal. “You’re creating this narrative to basically say, ‘look at this group, they’re so excellent. They’ve achieved everything.’ And pointing out to other minority groups: ‘that is what you need to be. And when you become that, that is only when we will talk to you.'”

Their friendship became an act of resistance in a business that rarely gave them a seat at the table. When it did, oftentimes it felt as if it was to fill a quota. Rarely do you see a “wave” of white designers splashed as a buzzy headline. “We are not a monolith,” says Lim. The vastly different ethnicities and experiences all lumped under the “Asian” umbrella should not be contained to a fashion spread revealed during A(A)PI Heritage Month. The Slaysians banded together to create strength and visibility. “It was important that we celebrate each other’s shows and show the public that we’re not competitors. We’re not what you’re trying to do to us and we’re gonna show you that we’re friends on and off the court,“ Lim continues. Now, the designers share once-sacred industry secrets, gossiping in their group chat about interactions with buyers and which factories in China to work with. “The reason why I launched bridal was because of Laura,” Gurung divulges, who also happens to be wearing 3.1 Phillip Lim boots.

For Leung, the only influencer in the group, her story is different but sings the same tune. As part of the first generation of style influencers (before influencers were even a thing), she noticed the current trend of fitting the mold for campaigns. One Black model. One white talent. And her. “I don’t want to be the chosen because of tokenism,” she says. “But I guess you can’t reach enlightenment or whatever without some pain first.”

The Slaysians found solace in solidarity, which was intensified by the pandemic as the group forged a quarantine bubble. They rallied to help create masks and jobs at the onset of COVID, rung in the new year together, took to the streets for Black lives (encouraged mostly by Gurung, affectionately nicknamed Protest Prabal), and most recently, started speaking out against anti-Asian hate. “When you’re a minority and you get this big job, big title, big opportunity, it comes with a massive responsibility,” Gurung says. “When we get a position of power, what are we going to do with it? It just can’t be for yourself.”

As Asians, they had all been encouraged to be quieter, both in their physical voices and on their runways. “If I never met them, I would have never posted anything on my Instagram regarding Asian hate. But the Slaysians taught me that I have a platform,” says Kim.

A week later after the dinner, Gurung relays a story: “I remember one collection was about this particular region between Tibet and China, where one woman can marry several men. I’ll never forget one person, a Fashion Director of an online platform, who said that if we want to see a collection about this, we will watch National Geographic. People are so crazy racist. People would ask to make it about St. Tropez, where people can understand. All my life, even within fashion, they’ve always tried to shut me down. And it was a battle that I was fighting alone. And then I met the Slaysians.”

While major ateliers stayed mum to the racism experienced by the Asian (American) and Pacific Islander communities, the Slaysians became fashion’s face of the movement. They banned together to create viral videos and raise funds for victims of assault. “It used to be about letting the clothes speak for themselves,” says Lim. “Now the clothes need to support your value system.”

“What’s disappointing is how the industry forgets, how celebrities forget. At one point we want to be all woke and stuff, but when it serves us, then we make it okay [to side with certain brands],” Lim relates. “I think what’s dangerous is when you’re fighting injustice for our community, and then you see what we saw during this past red carpet and the Oscars,” referring to liberal celebrities opting to wear clothes by designers with a trail of racist receipts. You vote with your dollar, and the Slaysians believe you dissent with your dress. And they’re not stopping the conversation any time soon, taking to their stories to discuss political topics. Lim’s non-profit brand New York. Tougher Than Ever, just launched a shirt to free Palastine.

“Our bond and connection and chemistry is way beyond us being Asian,” Williams tells me over the phone. “We’re like siblings. Whatever problems we have, we try to be there for each other.”

The alcohol at Flip Sigi flows free, but it’s not never-ending. As the night wanes, speeches slur and eyes glaze. Masks on, the Slaysians splinter. A few head home while others stumble off to a second location. Bound by fashion and food, a friendship that has only deepened in its short life, they are already in their group chat checking on each other.

When I ask them individually what their favorite Slaysian memory is, almost all share the same answer. Early in the pandemic sometime last April, an impromptu dance party turned dangerous when Gurung slipped and dislocated his shoulder. Together they scurried to the emergency room, spending the evening waiting until he returned fully repaired. Their friendship has cycles: from celebration to pain to healing. And then to the next meal.